A little over a month ago, Trinity’s leadership team began planning its response to what was then an imminent crisis. As recommended by our accrediting organization, the Southern Association for Independent Schools (@SAIS), we began planning our distance learning structure by first establishing our distance learning philosophy. We started with purpose, the why of what we do, before moving on to designing how we would deliver. It was then that Trinity’s leaders committed to our belief in foundation building and joyful learning. We decided that our goal would be to practice and develop foundational skills in a multi-sensory way. This philosophy has guided all decisions, policies, and supports around programming we have implemented since then. This philosophy has served as a source of pride when we are recognized for our framework’s intentionality and developmental appropriateness. It has also grounded us when our decisions around expectations and engagement have been called into question. Now that distance learning through the remainder of this school year has been made official by many schools or stated as highly likely by others, many parents will need to reframe their thinking and establish sustainable work-from-home and distance-learning practices. We are beyond the place where anyone can reasonably consider this time away from school an extended holiday. It is time to think about how we will move learning forward as much as can be expected, given the circumstances. The thought of distance learning, especially while working from home, is unbelievably daunting for so many. In response, I suggest that each family begin with their own philosophy or style and then build their schedule around that.

Over the past three weeks, Trinity’s Academic Leadership Team has received valuable feedback from our families about their circumstances and desires. While we seriously consider all of the feedback, it is always viewed through the lens of our distance learning philosophy. Because family requests have ranged from those that would have teachers provide all lessons online synchronously all day to tearful pleas that we send no more than one assignment a day, we know that every family is facing different challenges and working with different dynamics. I share this to say that your school cannot create the framework you need, because it will not be the framework that is appropriate for many others. So how do you identify your distance learning style and create a structure or schedule around it?

Every family has a culture, similar to the way every organization has a culture. This is not culture related to ethnicity, geographic region, or religion, although all of those things likely influence your family culture. I mean your family’s personality and ways of being, your spoken and unspoken norms and beliefs. Begin by thinking about what is most important to you about your child’s education and your work based on your family’s culture.

Next, consider your context. What resources do you have in terms of technology, child care, and time? How much flexibility do you have with any of your resources?

Finally, think about where you need to be on the continuum of stability and flexibility as well as interdependence and independence. The What’s Your Family’s Distance Learning Style? infographic is built around these ideas and can help families establish the beginning of a framework to suit their beliefs.

I also recommend an excellent article published in Harvard Business Review entitled 3 Tips to Avoid WFH Burnout. It offers suggestions for compartmentalizing responsibilities, managing time, and prioritizing tasks while working from home and facilitating distance learning.

I leave you with a quote I heard today while meditating with the Calm app (one of my practices for self-care). I wish you peace in creating a work-life structure that is true to your beliefs and truly sustainable.

“Peace. It does not mean to be in a place where there is no noise, trouble or hard work. It means to be in the midst of those things and still be calm in your heart.”

unknown

Citations:

Giurge, Laura M., and Vanessa K. Bohns. “3 Tips to Avoid WFH Burnout.” Harvard Business Review, 3 Apr. 2020, hbr.org/2020/04/3-tips-to-avoid-wfh-burnout.

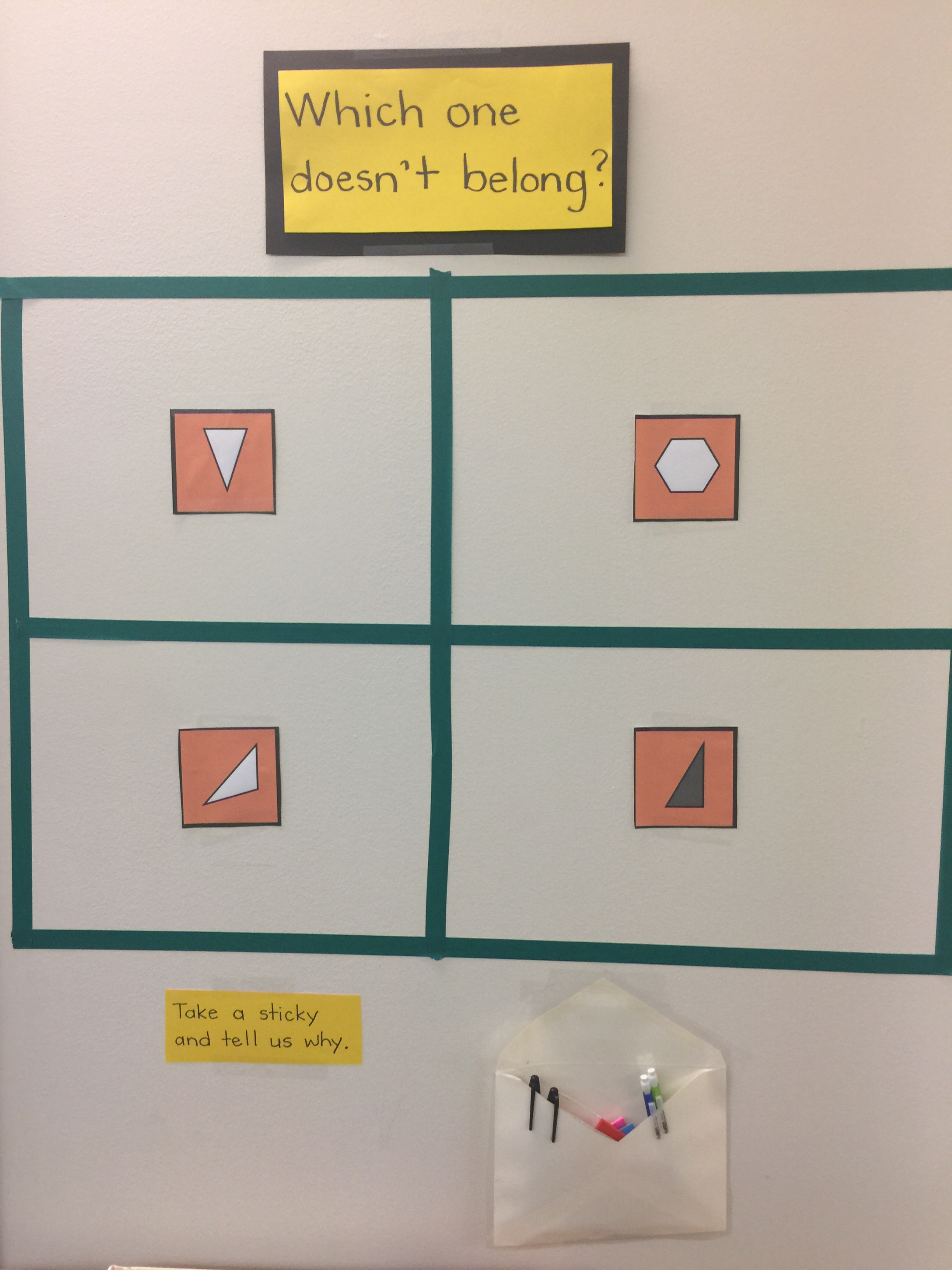

One of my favorite math games for making student thinking visible and developing the mathematical practice of constructing a viable argument is called “Which one doesn’t belong?”, originally created as a children’s picture book by Christopher Danielson. The book contains sets of pictures that prompt students to notice the properties of shapes and then provide justification for their observations about which one doesn’t belong with the others. The best part about the activity is that there is no one “right” answer. There are many ways that one can justify their answer, allowing students to hear different perspectives and consider new ways of thinking. With puzzles that extend far beyond shapes, the activity has become wildly popular. People across academic disciplines regularly share new ideas and thinking on social media through

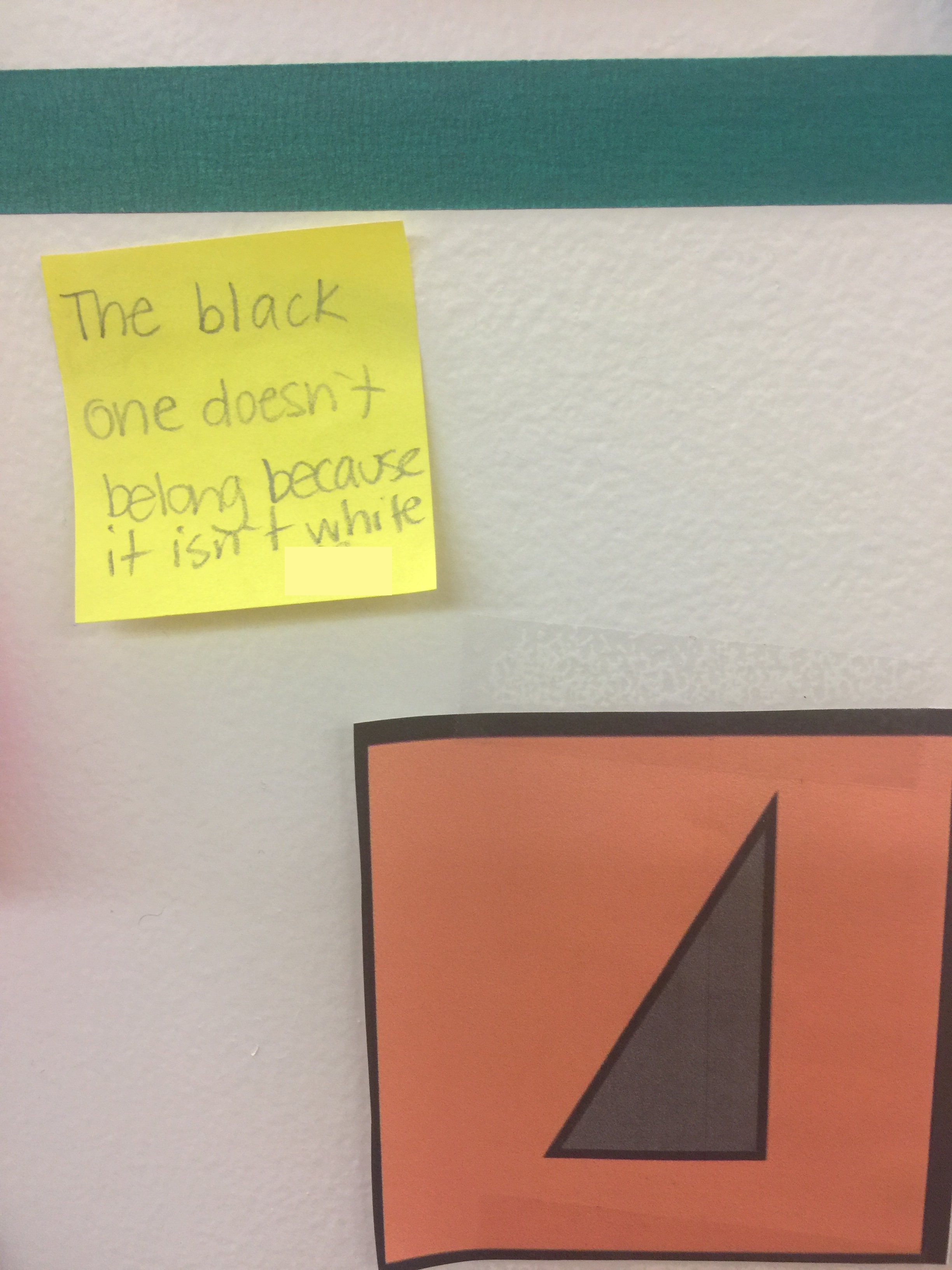

One of my favorite math games for making student thinking visible and developing the mathematical practice of constructing a viable argument is called “Which one doesn’t belong?”, originally created as a children’s picture book by Christopher Danielson. The book contains sets of pictures that prompt students to notice the properties of shapes and then provide justification for their observations about which one doesn’t belong with the others. The best part about the activity is that there is no one “right” answer. There are many ways that one can justify their answer, allowing students to hear different perspectives and consider new ways of thinking. With puzzles that extend far beyond shapes, the activity has become wildly popular. People across academic disciplines regularly share new ideas and thinking on social media through  I love what this activity does to develop critical thinking and communication skills. So, I struggle with the lingering feeling of unease that I have maintained since the very first time I watched a teacher facilitate the activity with a group of young students. It’s the language. “Which one doesn’t belong?” is difficult to accept when looking out at a classroom full of children that are moment-by-moment authoring their identities with the language we use. My unease became further strengthened as I witnessed a group of Pre-K students looking at a “Which one doesn’t belong” poster, and I found myself sympathizing with the one African American child in the group listening to someone say “the black one doesn’t belong because it isn’t white”.

I love what this activity does to develop critical thinking and communication skills. So, I struggle with the lingering feeling of unease that I have maintained since the very first time I watched a teacher facilitate the activity with a group of young students. It’s the language. “Which one doesn’t belong?” is difficult to accept when looking out at a classroom full of children that are moment-by-moment authoring their identities with the language we use. My unease became further strengthened as I witnessed a group of Pre-K students looking at a “Which one doesn’t belong” poster, and I found myself sympathizing with the one African American child in the group listening to someone say “the black one doesn’t belong because it isn’t white”.